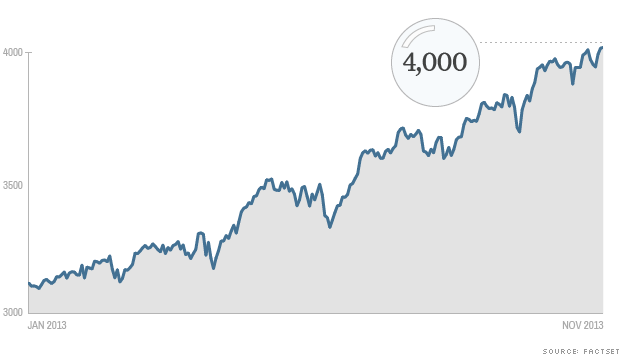

Market analysts say this Nasdaq run-up is nothing like the tech bubble of 13 years ago.

NEW YORK (CNNMoney)

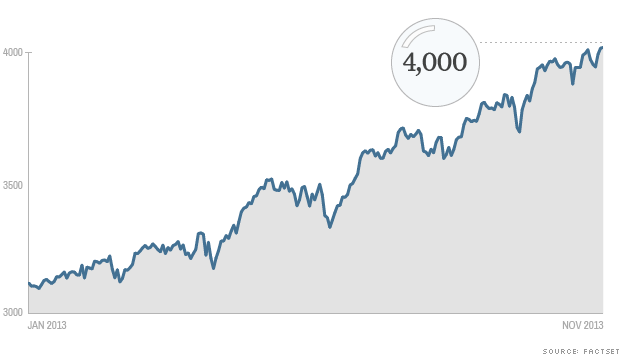

It makes sense that benchmarks like the Nasdaq at 4,000 could reignite bubble fears. It comes after the recent string of successful initial public offerings from unprofitable companies like Twitter (TWTR), and reports of startup Snapchat turning down a $4 billion buyout -- despite bringing in no revenue.

But analysts say the rush to call a tech bubble, while understandable, isn't grounded in reality.

"Anytime you have a substantial run in an asset -- especially one like the Nasdaq ... you can't help but ask the [bubble] questions," said Drew Nordlicht, managing director at asset management firm HighTower Advisors. "But there are big divergences between now and the tech bubble of 2000."

2000 vs. 2013: The biggest difference between now and then: The hype in 2013 is fairly muted compared with the dot-com heyday.

Sure, Facebook's (FB, Fortune 500) IPO may have been overhyped, and select startups will continue to raise money at seemingly astronomical valuations. But analysts insist the exuberance level doesn't even come close to the old days.

"In 2000, people said the [dot-com boom] was on par with the Industrial Revolution -- we were going to be living in one of those sci-fi movies," Nordlicht said. "We don't have that level of a mass fever pitch today."

Todd Salamone, senior research VP at Schaefer's Investment Research, agreed.

"There was a 'sky's the limit' mentality in 2000, in terms of revolutionary technology leading to productivity enhancements," Salamone said. "There was no prediction that was too high. Today there is a lot more hand-wringing, more caution."

By the numbers: It's not just about irrational excitement: Tech company valuations this time around simply don't rival those of 2000.

Back in 2000, a person would hardly blink an eye at a company like Cisco (CSCO, Fortune 500) trading at 66 times earnings estimates for the coming year, said Nordlicht, the HighTower managing director.

These days, Cisco's price-to-earnings ratio is hovering below 12 -- near that of mighty Apple (AAPL, Fortune 500). Even Google (GOOG, Fortune 500), which has generally reported strong earnings this year and is poised to overtake Exxon Mobil (XOM, Fortune 500) in market capitalization, is trading at 24 times earnings expectations for next year.

While the Nasdaq does have outliers like Netflix (NFLX) trading at more than 200 times earnings, such high ratios aren't the norm -- and the broader index are much more grounded in reality than 13 years ago.

"These ratios aren't levels that have defined peaks in the past," said Salaome, the Schaefer's senior research VP. "Far from it."

Price-to-earnings ratios soared so high in 2000 because "people were buying companies based on future prospects -- where you expected them to be a in a decade," Nordlicht said. "You don't see that today. Even if people aren't demanding profitability right now, they want to see a road that leads to profit."

Related story: 8 things to know about the 2013 bull market

A slower rise to 4,000: Looking at the Nasdaq's overall gains, Salamone pointed out the 1999-2000 run-up was "parabolic": The index hit 3,000 in November 1999 and topped 4,000 the following month, before reaching a high above 5,000 in March 2000.

"Today's move is not what I would call parabolic," Salamone said. This time around, the Nasdaq took nearly a year to jump from 3,000 to 4,000.

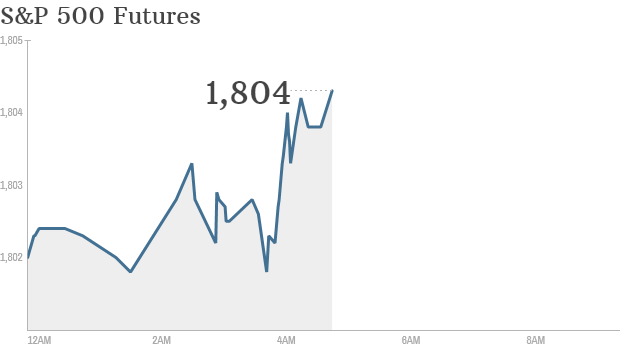

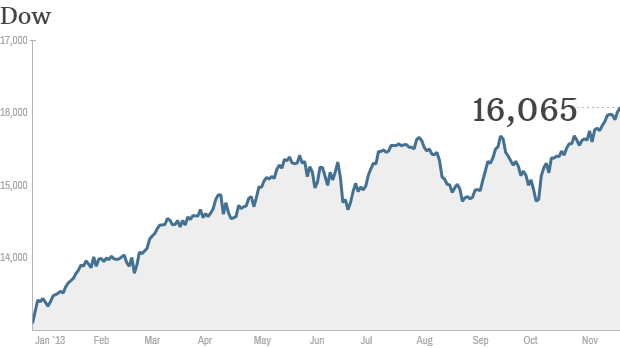

What's more, the Nasdaq has risen along an overall 2013 bull market, on stronger macroeconomic conditions: the Federal Reserve's bond-buying program, the overall improving economy and low earnings expectations. The Nasdaq's 32% gain so far in 2013 is only six percentage points above that of the S&P (SPX) 500 index, and ten points above the Dow's (INDU) jump.

Startups will continue to raise gobs of cash, and select tech sectors like social-media stocks may get rather frothy. But the established techs in the Nasdaq -- and the index's gain -- aren't where to look if you're trying to prove a bubble.

In fact, Salamone thinks the memory of 2000 is still too fresh to let the excitement soar into bubbly exuberance.

"In 2000, everybody looked back and was shocked by how badly they were burned," he said. "Now everyone's afraid of that happening again -- and it's hard to have a bubble when everybody fears a bubble."

First Published: November 27, 2013: 3:48 AM ET

![]()